Understanding

Understanding |

|

Vionnet |

I’ve been trying to buy a copy of Betty Kirke’s very-hard-to-find book on the designer Madeleine Vionnet for years now.

Anybody who knows anything about publishing will tell you that books about fashion don’t make money. Doesn’t matter how good they are, people just don’t buy them. (Well, unless you count The Devil Wears Prada.)

So I was impressed when an online book dealer offered to sell me a publisher’s remainder of Madeleine Vionnet for just under $1,500 last year. Not bad for a remaindered book about a dead dressmaker most people have never heard of. Especially considering that it only cost $100 new in 1998.

I had scoured the internet. Only a few days earlier, in fact, www.amazon.com had sold me a copy for $115. And, just a couple months before that, I’d bought the same book from www.bookcloseouts.ca for a mere $35.79.

Which would’ve been a real bargain. Except that, a few weeks after I bought it, bookcloseouts emailed to say that my $35.79 copy had turned out to be “defective,” so they’d had to run it through the pulping machine.

And maybe they did.

Or maybe somebody noticed that even beat-up used copies were selling on eBay for upwards of $500, so why should I get an only-slightly-damaged one for $35?

The $115 copy never showed up, either.

Happily, Kirke’s publisher, Chronicle Books, has finally reprinted Madeleine Vionnet. The book itself, a painstakingly researched monograph on the work of a dressmaker who never put her logo on anything, is an unlikely blockbuster: No dish, no scandalous revelations, no drugs, no sex, no bad behavior. It’s all about the clothes Vionnet made and how she made them.

Now, so much of your sense of a designer’s importance depends on extraneous factors—trendiness, movie-star clients, marketing budgets, perfume sales—that the clothes themselves can seem secondary. How do you understand a designer who’s remembered purely for the structure of the dresses she made?

Everybody knows Chanel. Judith Krantz wouldn’t’ve dared make up Gabrielle Chanel’s orphan-to-kept-woman-to-girlfriend-of-the-Duke-of-Westminster personal life. Not that her clothes weren’t great, but never underestimate the effect of a zillion-dollar ad budget: Chanel lives because House of Chanel zillionaire owners Alain and Gerard Wertheimer have—with significant help from Karl Lagerfeld—kept the label alive and kicking.

By contrast, since Vionnet retired in 1939, nothing but perfume--and precious little of that--has been sold under her name.

Madeleine Vionnet opened her couture house in Paris in 1912 after a 25-year apprenticeship. She had wanted to be a teacher but education past the primary grades cost money, so she left school at 11 to be apprenticed to a seamstress. For the 25 years before she went out on her own, she worked as a dressmaker, sample maker, patternmaker and design assistant at other houses. (Imagine: A fashion designer who knew which end of the needle was which! None of this flipping through the L.L. Bean catalog, fiddling with the fit and cranking up the colors.)

Kirke, a clothing designer turned costume conservator, discovered Vionnet in 1973 when the Metropolitan Museum, where she worked, was preparing an exhibition called Inventive Clothing, 1909-1939. An evening dress slated for the show—it was short in front, long in back--caught her eye because it looked so contemporary: “It could have been worn out that very evening.” She pegged it as a Balenciaga, but no: Vionnet had made it in 1917, when young Balenciaga was still picking up pins as apprentice to a provincial dressmaker in his native Spain.

When she examined more Vionnet dresses in the Museum’s collection, Kirke was amazed and fascinated: They were cut in a way “completely different” from the other clothes in the show, and each of them was “thought through to the smallest detail.”

According to the usual capsule bio, Vionnet “invented the bias cut.” But it’s not so much that she invented it as that she learned what it did. She devoted her working life to experimenting with cloth and studying the way it behaved under various constraints. What she learned about the subtleties of bias allowed her to do things with fabric that never occurred to other dressmakers. Her dresses slide over the body, wrap, fall, flow, swirl in a way that looks natural, effortless: Vionnet’s art freed the fabric to do what it wished.

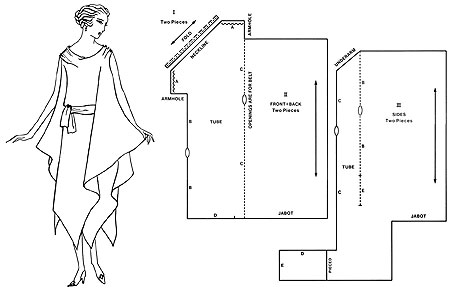

Kirke’s book pays the same kind of fierce, informed attention to the structure of Vionnet’s clothes that the designer herself paid to the physics of fabric. Lots of writing about fashion is heavy on adjectives like divine, fabulous, enchanting; this book has diagrams of the patterns of Vionnet’s ingenious dresses.

Kirke isn’t a fashion writer. “Her business isn’t writing, her business is Vionnet,” says Anne Bissonette, curator of the Fashion Museum at Kent State University Museum. An exhibition on clothing design and construction on view at that museum through next September features some of Kirke’s reproductions of Vionnet designs along with diagrams of the patterns they were made from.

Kirke uses sketches and diagrams like these, of a Vionnet dress cut on the straight grain and hung on the bias, to show what made Vionnet's dresses work so brilliantly. Sketch and diagram from Madeleine Vionnet by Betty Kirke, Chronicle Books.

Kirke uses sketches and diagrams like these, of a Vionnet dress cut on the straight grain and hung on the bias, to show what made Vionnet's dresses work so brilliantly. Sketch and diagram from Madeleine Vionnet by Betty Kirke, Chronicle Books.

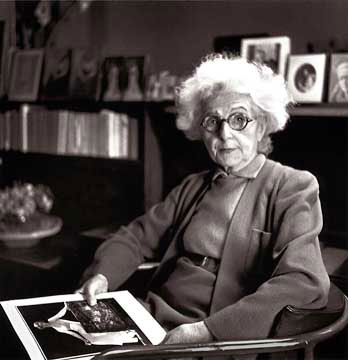

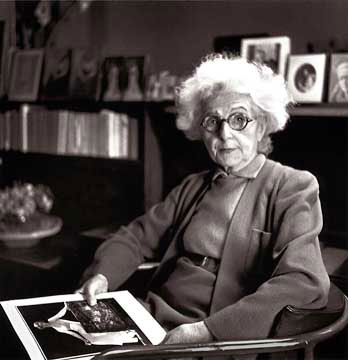

Bissonette says Kirke is “the only person who could have done this book.” She was “uniquely placed because she was a designer, then became a costume conservator.” Plus “she’s one of the few people left who actually met Vionnet and asked specific questions about construction.”

As Kirke explained in an article in Threads Magazine in 1989, and then in the book itself, she met Vionnet on a visit to Paris in the early 1970s. The designer was 98, too fragile to give long interviews, but she offered Kirke access to her own wardrobe. She invited her to try on anything she wanted, and to borrow anything she wanted to copy. Kirke measured the warp and weft of each piece of each dress, Bisonnette says, to be able to determine exactly how each garment was cut and assembled, and then graphed the results.

Naturally, once she had derived the patterns from Vionnet’s clothes, nobody wanted to publish them. People expected fashion books to have pretty pictures and lots of adjectives, not diagrams.

But it’s the diagrams that make the book a cult object. It’s the patterns that allow you to see exactly what Vionnet was doing. They make it a book you want to read with scissors in hand and a pile of old sheets at the ready, so you can cut out the shapes and see what they do when you put them together.

Bissonette says it’s “the best book done in the past 50 years about costume.” The state of the copy I borrowed from the Drexel University Library backs her up. It’s big enough to be a coffee table book, but its binding is almost worn out from use. Happily, now it can be replaced.

And now I can have one of my own.© 2005 Patricia McLaughlin